You could not just do as you pleased with religious art in the 17th century, and even more so because the Church had only recently emerged from a major crisis.

During the previous century, Europe was divided into two camps: Catholics, who respected the Pope’s authority and Protestants, who questioned it. From this point on, the two could not be reconciled.

Religious art was precisely one of the things they disagreed on:

The religious opposition between Catholics and Protestants was also present in the field of art.

This was perfect, since the baroque art of the 17th century was completely in line with the ideas of Catholics.

To hell with the reasoning of the Renaissance, baroque art aroused feelings. To move viewers, artists mixed the different styles of art, preferring dramatic scenes and trompe-l’œil effects. Their exuberant works are a feast for the eyes.

However, baroque art was not alone in this. In some European countries, the public continued to enjoy the balance and tranquility of more “classical works”.

These two 17th century movements therefore had to live alongside each other, sometimes in the same building!

During the 17th century in Europe, exuberant gothic art existed alongside a more classical, peaceful style.

Art did not serve only the Church. It was also used by many monarchs for their own glory.

These three artists worked for them.

Monarchs called on the services of artists such as Rubens, Velázquez and Le Bernin to create works of art for their own glory.

During the 1660s, Le Bernin left Rome for Paris, exceptionally. The French king wanted to rebuild the façade of the Louvre Palace. In so doing, he seized the opportunity to landscape the surrounding land, as could be expected of a good urban planner.

Architect Le Bernin’s project for the façade of the Louvre was not to the taste of the king, who preferred the more classical design of a colonnade.

It was indeed the case that new institutions saw the light of day in 17th century France. They were academies, which had the King’s personal protection. Like their Italian counterparts, their purpose was to train young artists. Science, literature and practical skills were all training topics, to equip them fully for success.

The French academies trained young artists and defined a hierarchy of “genres” in the field of painting.

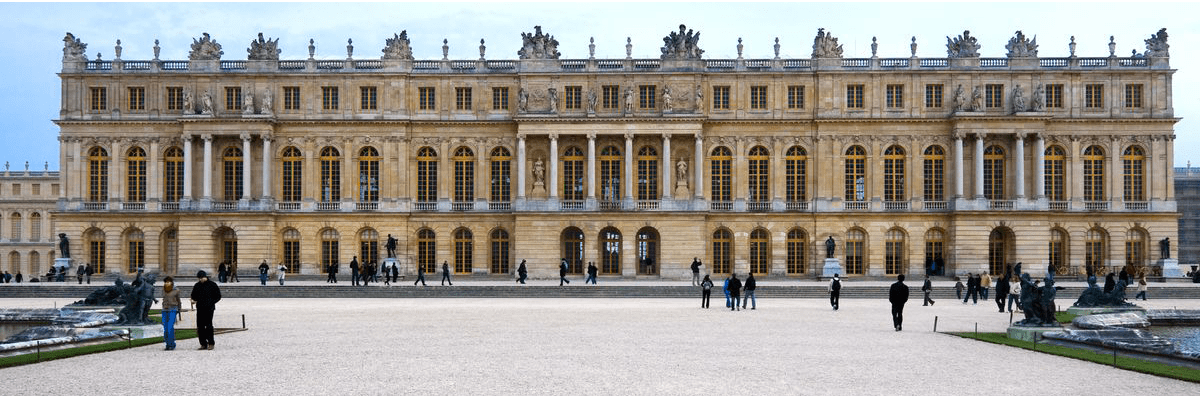

King Louis XIV was not content to simply supervise the academies. He also wanted to have a castle to reflect his “glory”: this was to be the famous palace of Versailles.

Its designers leaned towards the “classical” styles, with their colonnades and mythological decorations, although the overdone painting and sculptures inside were more a reflection of baroque style. After all, why choose between the two?

The King was the centre of this miniature universe. His grand Hall of Mirrors was a celebration of his military power and artistic taste.

Versailles Palace, built during the reign of Louis XIV, combines baroque style interior decorations with a more classical style outside.

A breath of freedom swept across Northern European countries, with a total absence of hierarchy between painting “genres”, or a monarch to use the artists’ work for his or her own ends.

Selling one’s work was, however, still necessary in order to make a living. This meant that painters had to accept orders from bourgeois clients, who were often merchants, and who were not fond of vast historical scenes, preferring happy charming scenes to adorn the walls of their houses.

The result was an over-abundance of portraits, landscapes and other scenes from daily life.

In Northern European countries, painters did portraits, landscapes and other “genre” scenes for their bourgeois clients.

"*" indicates required fields