To get to Land Art, Robert Smithson first went through Minimalist Art. What’s that? It was an American movement during the 1960s that sought to remove the personality of the artist from the work of art.

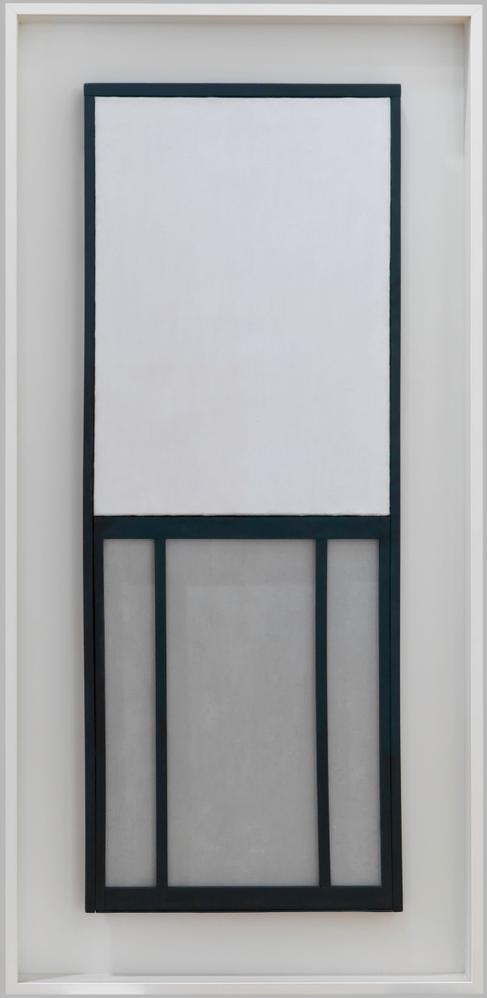

Ellsworth Kelly is considered to be one of the precursors of this movement. Everything started with a strange experience in Paris.

“In October 1949 at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, I noticed the large windows between the paintings interested me more than the art exhibited. I made a drawing of the window and later, in my studio, I made what I considered my first object, Window, Museum of Modern Art, Paris. From then on, painting as I had known it was finished for me. The new works were to be paintings / objects, unsigned, anonymous.”

Following on from Kelly, many artists continued the work of Minimalist Art.

Ellsworth Kelly was one of the pioneers of minimalist art, who tried to remove all trace of the author’s personality from his works.

Frank Stella, one of the founders of Minimalism, created paintings with repetitive subjects, but in totally original formats.

Like the painters, Minimalist sculptors wanted to set artistic creation free from the personality of the artist. In short, to make art anonymous.

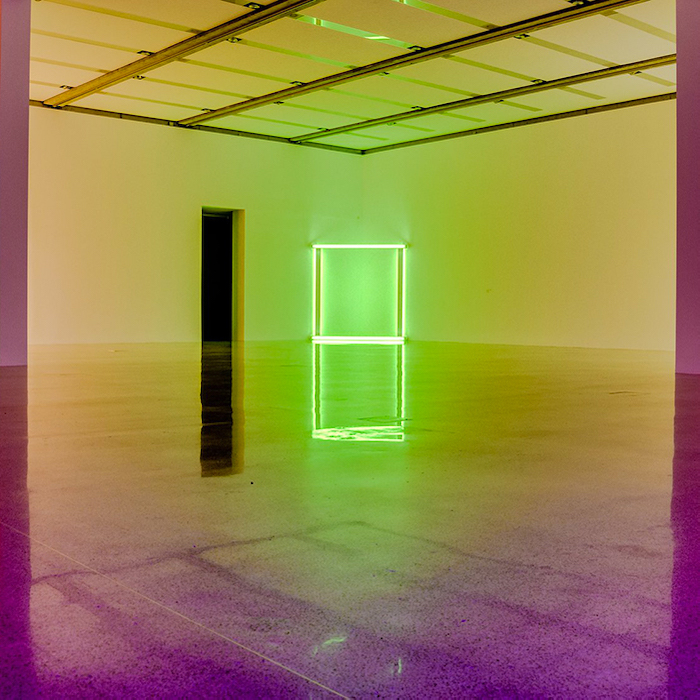

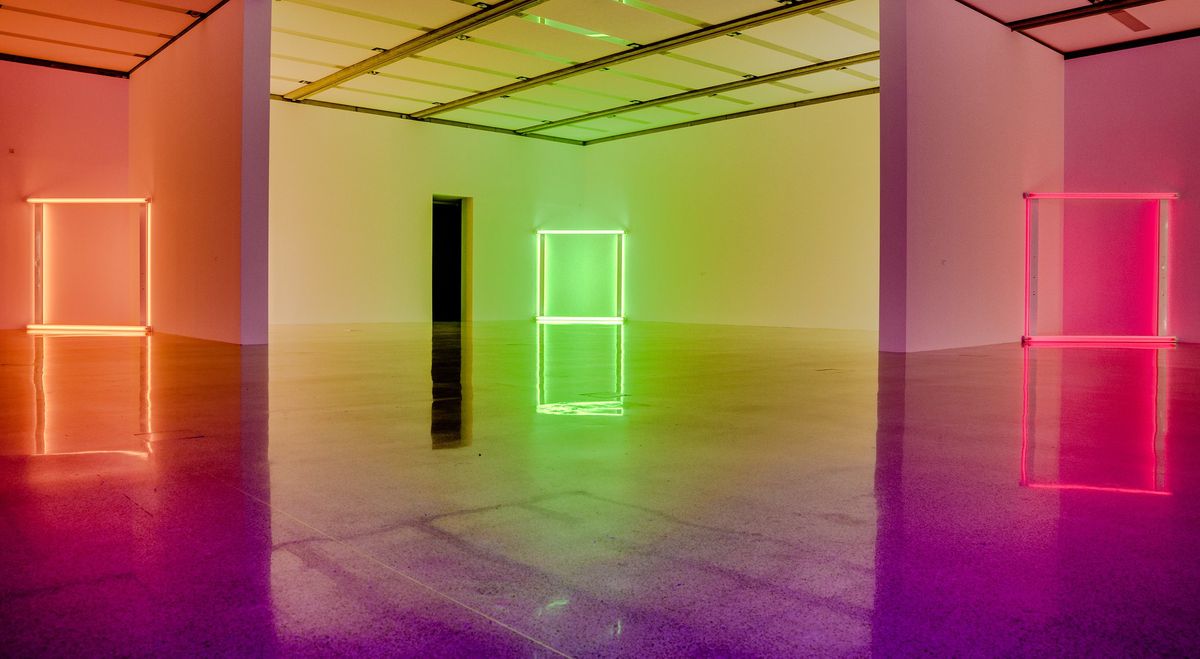

Through this work, Dan Flavin made himself a light sculptor. The neon light cut the corner of a wall. The colours blended to create an intangible painting, spreading wider than its frame.

Flavin chose materials manufactured in factories to create his work of art. Going even further, he limited his role as an artist to designing the work on paper. He then entrusted the sketches to technicians, who made them.

Dan Flavin designed impersonal works which were light sculptures and made by technicians.

From the beginning of the 20th century, sculpture had greatly changed. Artists began by gathering together objects, but they had also used waste, animal bones or vegetable materials.

During the 1960s, a large step forward was taken with the appearance of sculptors such as Dan Flavin. For these artists, the place chosen for the exhibition belonged to the work.

The term used then became installations. Flavin’s example helps us to understand what this changed.

The work uses objects that were not manufactured as part of a work of art (for example neon lights).

It has no real spatial limits: the light is diffused all round.

The presence of the work changes our perception of the space where it is exhibited.

From the 1960s, a work of art was also designed to modify our perception of the place where it is presented: this is known as an installation.

In France, from the 1940s, Vasarely also limited his works to lines of paint and geometrical shapes. At the time, this painter was almost the only one to take this new artistic direction, but twenty years later, he became the leader of a new movement: Op Art.

Op Art (Optical Art) is based on the knowledge of human vision. In fact, our eye sends its perception to the brain, which interprets it, based on its experience. Op Art artists “trompe” (deceive) it (trompe l’œil), making it believe that their paintings have relief, rising out of the flat surface of the canvas.

Op Artists like Vasarely use geometrical shapes to create optical illusions for the viewer.

At the end of the 1960s, an Italian movement made these artistic installations its speciality: Arte Povera (poor art).

For its artists the act of creating was more important than the finished works and their creations are sometimes impossible to keep.

In fact, Arte Povera artists led a revolt against the art world. They wanted to be able to create without the help of the galleries or museums, so they kept their material and financial needs for their works to the strict minimum. This is where this name “poor art” comes from.

Italian Arte povera brought together artists who rebelled against the galleries: they created their works of art from very little.

Who could present themselves today as the heir of the artists presented here? Several artists could doubtless do this, but one of them is at the crossroads of several paths: Olafur Eliasson. For him, the viewer’s feelings and, in fact, everything to do with the senses, is the core of art.

Each one of his works was a journey from which travellers returned different from when they started it.

Olafur Eliasson, New York City Waterfalls,

2008, installation, Brooklyn Bridge, New York. Photo: Wally Gobetz, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Olafur Eliasson, Weather Project,

2003, installation, Tate Modern, London. Photo: wonderferret, CC BY 2.0

Olafur Eliasson, Eye see you,

2006, installation planned for Louis Vuitton shop windows. Photo: samu szemerey, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Through his installations, Olafur Eliasson worked on the viewer’s feelings, in an extension of Land Art, Minimalist Art and Arte povera.

"*" indicates required fields