As the history of western art evolved, the subject matter of paintings became known as “genres” and some were considered more important than others.

These genres had a hierarchy which became established in the 17th century by the French Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux-Arts). It went as follows…

In first place was history painting, featuring subjects from classical history, mythology, and the Bible, as well as more recent historical events. Next up was portraiture, capturing the great and the good, followed by genre painting, with a focus on scenes of everyday life, such as people having a party or going to the market (not to be confused with the term “genre” described above).

Trailing in fourth place, was landscape painting, and then, finally, the lowly still life, at the bottom of the heap. Landscape and still life did not feature people and so were seen as far less important.

In the 17th century still life was seen as the least important genre in art, after history painting, portraiture, genre painting and landscape.

This is a still life. But what does that mean? That the objects are still? Yes. That they do not move? Yes. That it is a representation of life, so it shows things that are alive? No. Well, sometimes yes, but often they are dead, or dying.

In essence, still life is a subject in art that refers to anything that does not move – an inanimate object which can be natural or humanmade, or, frankly, dead.

But where does the term come from?

While still life as a subject in art has been around for literally ages – for example, it has been found in Ancient Egyptian tombs, and pops up all over the place in medieval and Renaissance altarpieces; it only became used as an actual term in the 17th century Netherlands.

The English term “still life” stems from the Dutch “stilleven”, which means “quiet life”. The French called it nature morte and in Italy it became natura morta which both mean “dead nature” – except, remember, not everything in a still life is dead…

The term “still life” started to be used in the Netherlands in the 1600s. It comes from the Dutch stilleven, which means “quiet life”.

Still life has survived as a genre for centuries, dating back to tomb paintings in Ancient Egypt, and mosaics and frescoes in Ancient Greece and Rome.

Still life paintings tend to fall into five main categories. One of these is food and drink, often laid out as a sumptuous banquet, or as the remains of a simple breakfast.

The objects can tell us about the social status of who owned the painting, as well as about a particular time and place. For example, let’s look at the still life on the left. By featuring a lemon from the Mediterranean, and a gently twisting jug made out of Venetian glass, the artist is showing us the global trading power and prosperity of the Dutch Golden Age.

It looks like whoever lived here knew how to have a good night in! Household objects that point to pleasures and pastimes – such as wine, books, maps, jewellery, and musical instruments – are also featured in still life paintings.

Another popular theme is flowers, often in spectacular arrangements where the species on display couldn’t possibly have been in season at the same time, as in this wonderful painting by Jan van Os. Alongside a blossoming (ahem) international trade in bulbs in the 1600s, a huge interest in botany grew (get it?).

Or take Vanessa Bell, a prominent figure within the Bloomsbury group (a group of associated English writers, intellectuals, philosophers and artists in the early 20th century), who explored flowers as symbols for beauty, vitality and sorrow. In her post-WWI painting “Chrysanthemums”, she painted flowers typically associated with death and grief to capture the widespread mourning felt by nations who had lost lives during the war.

Let’s not forget some of the most iconic artworks of all time, Vincent van Gogh’s series of sunflower paintings. Surely, this glowing expression of hope and emotion shifts the humble still life genre into the premier league?

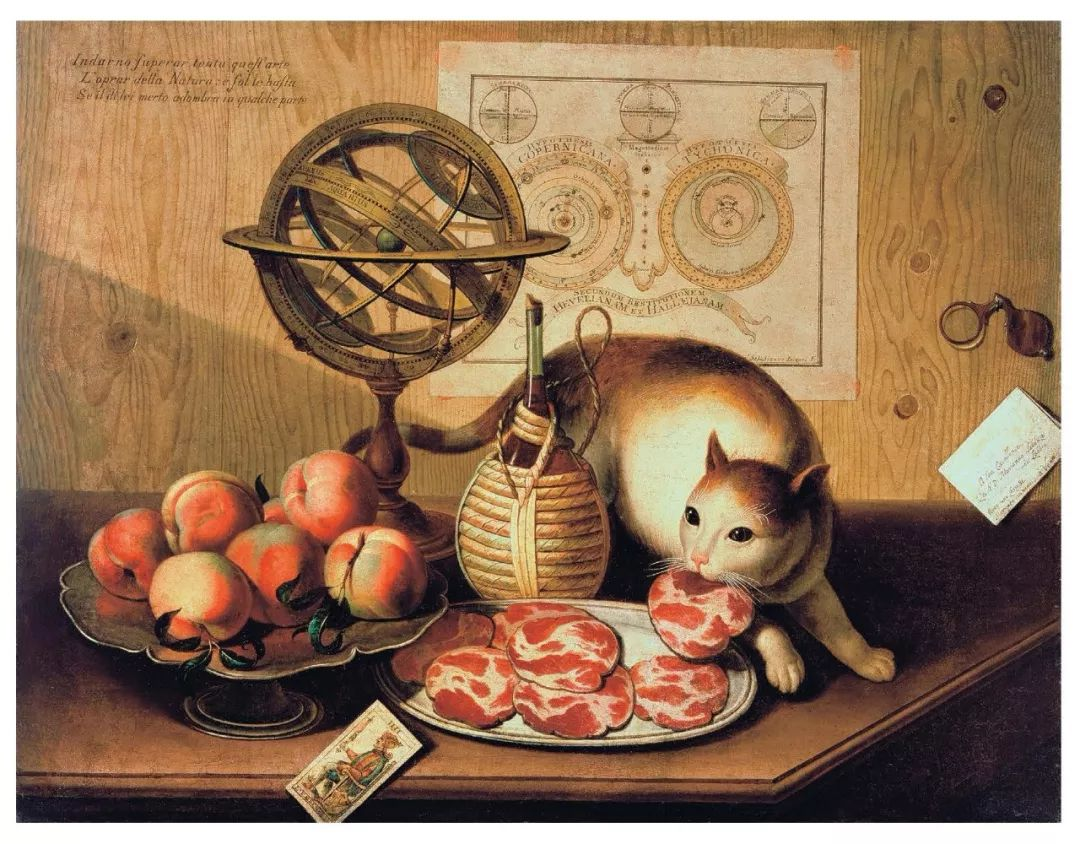

Then there are animals. In most cases the animals are dead or will be eaten, such as hares or birds being hung to develop their flavour. In other paintings, animals such as cats or dogs are introduced to bring a sense of movement or drama, such as in Sebastiano Lazzari’s Still Life with a Cat.

Still life has five main categories: food and drink, household objects, flowers, animals, and symbolism.

Still life was not just a vehicle for artists to flaunt their dazzling technical skills; it also allowed them to show objects with symbolic meaning. For example, ripe grapes and blossoming roses were not just objects of beauty and pleasure, but a reminder of the fleeting nature of life, for they will soon rot and die. Cheery.

This kind of artwork, which sets out to remind us of our own mortality, is called a memento mori or vanitas. While these terms are very similar in meaning, each has a slightly different nuance.

Memento mori is Latin for “remember you must die”. That’s a pretty direct message! Artists started to paint memento mori objects like skulls on the back of portraits during the 1400s and 1500s. By the 17th century it had become popular as a genre in its own right, particularly in Northern Europe, and was heavy with symbols like a snuffed-out candle or an hourglass.

Vanitas is Latin for “vanity”. As well as reminding us that our time on earth is temporary, vanitas paintings give an extra punch by setting memento mori symbols against the joys and trappings of material life.

In other words, don’t be too distracted by worldly pleasures like fine wine, music, and literature, as they are ultimately worthless. Nurture your soul and spiritual life, not just your body!

Memento mori and vanitas artworks remind us of the fragility of human life, and encourage us to look beyond material things.

As an incredibly versatile subject, artists have continued to use still life as a playground for expression and experimentation, as a place to try out new styles and techniques, and a way to break the rules.

Obviously, things have changed a lot since the 1600s. For example, in the early 1900s Cubist pioneers like Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris were dismantling the rules of painting by trying to show objects from different perspectives at the same time in the same picture.

Other artists, like French painter Fernand Léger and British artists Patrick Heron and Mary Fedden were using still life to explore light and colour through expressive brushstrokes and lively shapes of contrasting colour.

Artists had also started to use real objects in their work, which we’ll get on to later. So well done, still life, for sticking it out, and tipping convention – and ideas of hierarchy – on its head!

Still life as a genre lives on, spanning not only across art movements such as Impressionism, Cubism or Pop Art, but across times, places, and cultures.

"*" indicates required fields