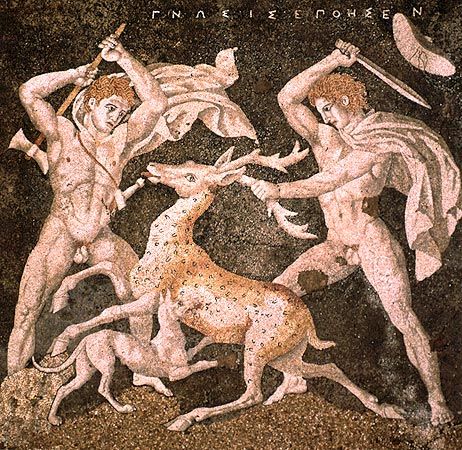

A strater in electrum in the name of Vercingetorix around 60 BC, French National Library, Paris

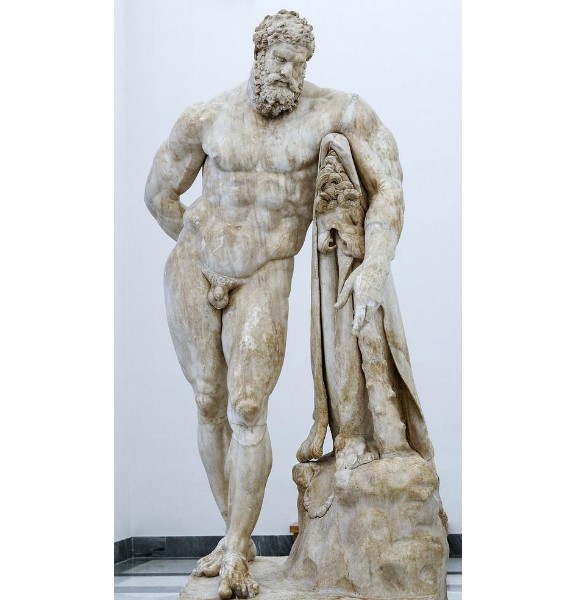

Vercingetorix

- The leader of the Gauls

- He made an alliance with the celtic peoples to resist the Romans

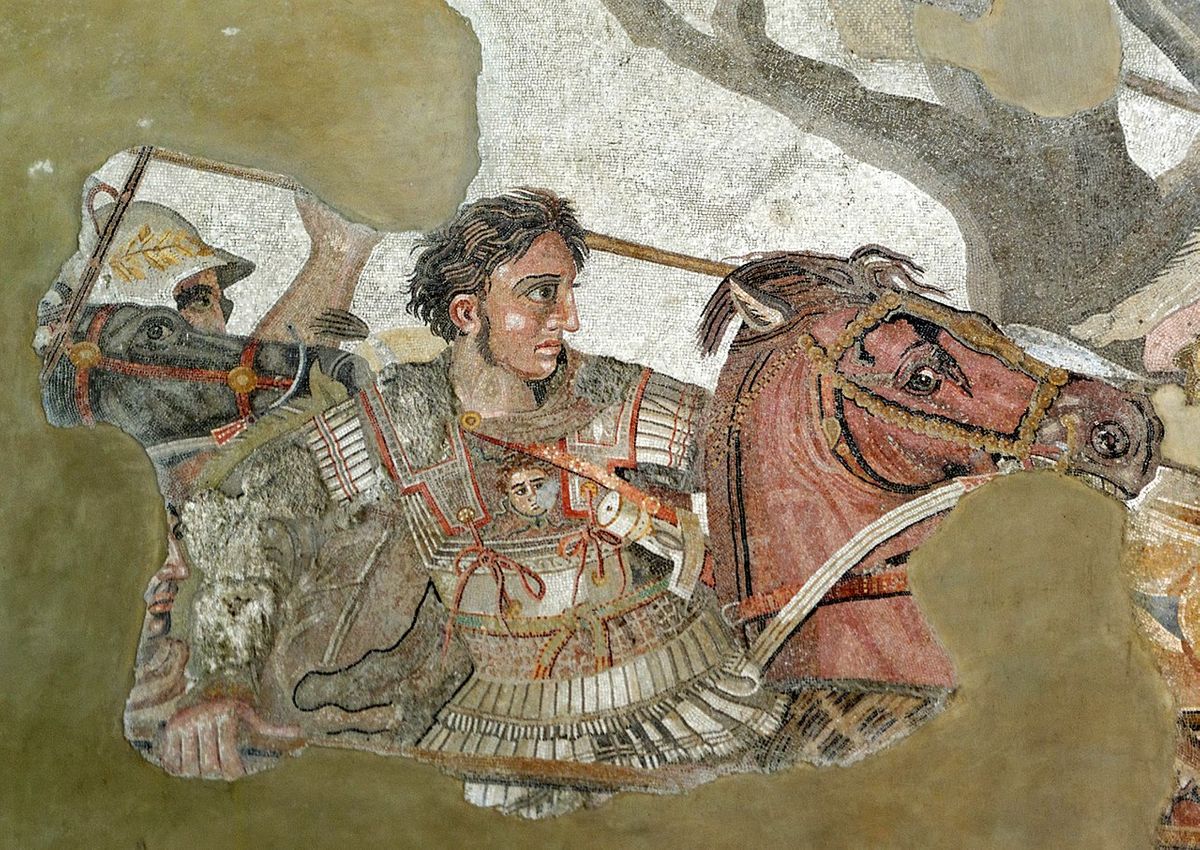

Denier, portrait of Caesar as perpetual dictactor around 44 BC, French National Library, Paris

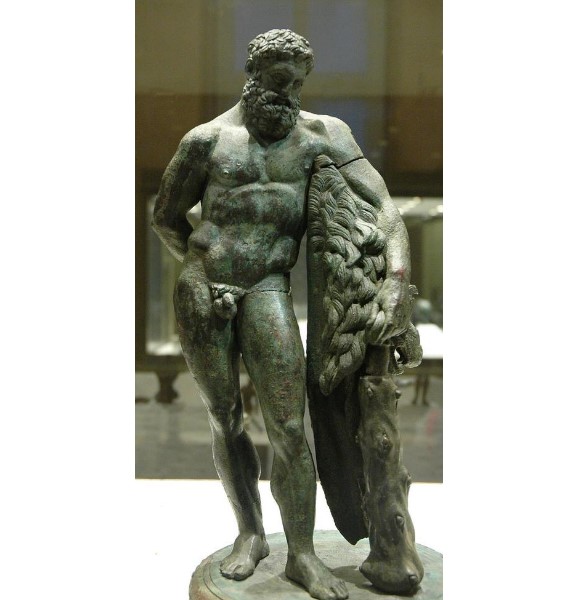

Caïus Julius Caesar known as Julius Caesar

- The Roman leader (please note that, contrary to popular belief, he was not emperor)

- He wanted to conquer Gaul for his own personal glory.