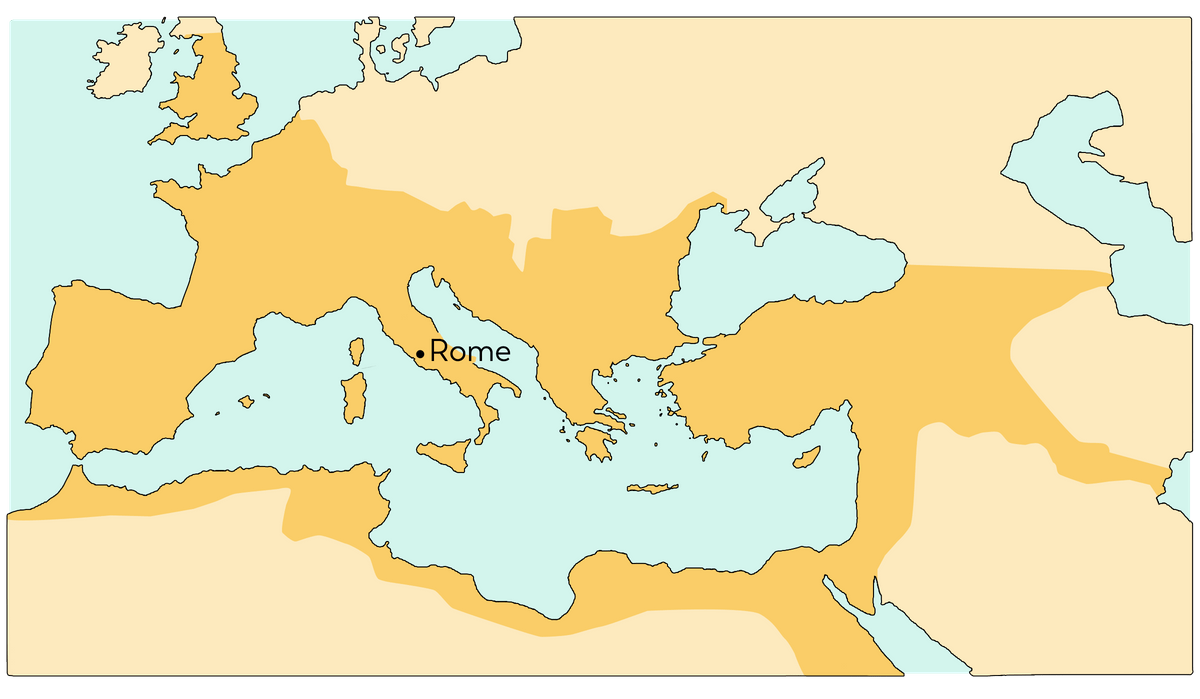

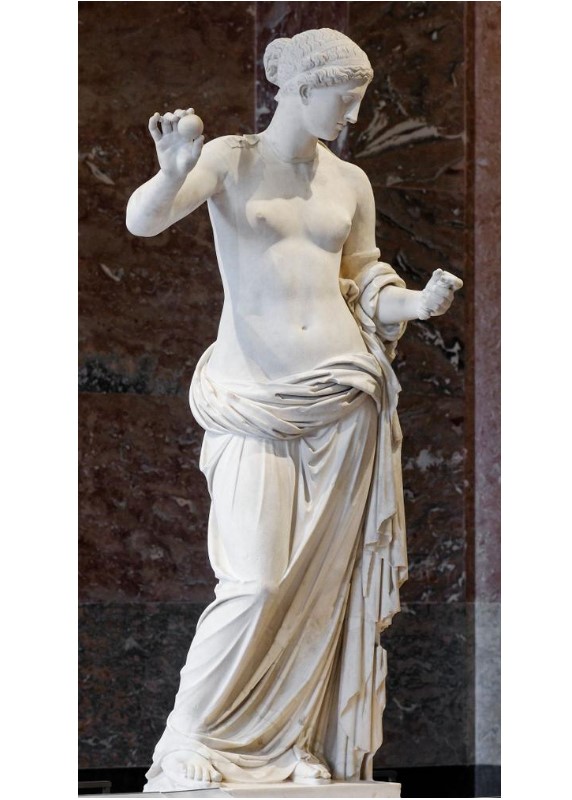

Venus of Arles,

late 1st century BC, marble, 76.4 inches (height), Louvre Museum, Paris. Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen, CC BY 2.5

Venus

Distinctive Sign: Often naked, with a seashell or a dove

Profession : Goddess of love and beauty

Key fact: She has numerous extremely beautiful children, including Eneus, not always by her husband, because she and Mars are lovers.

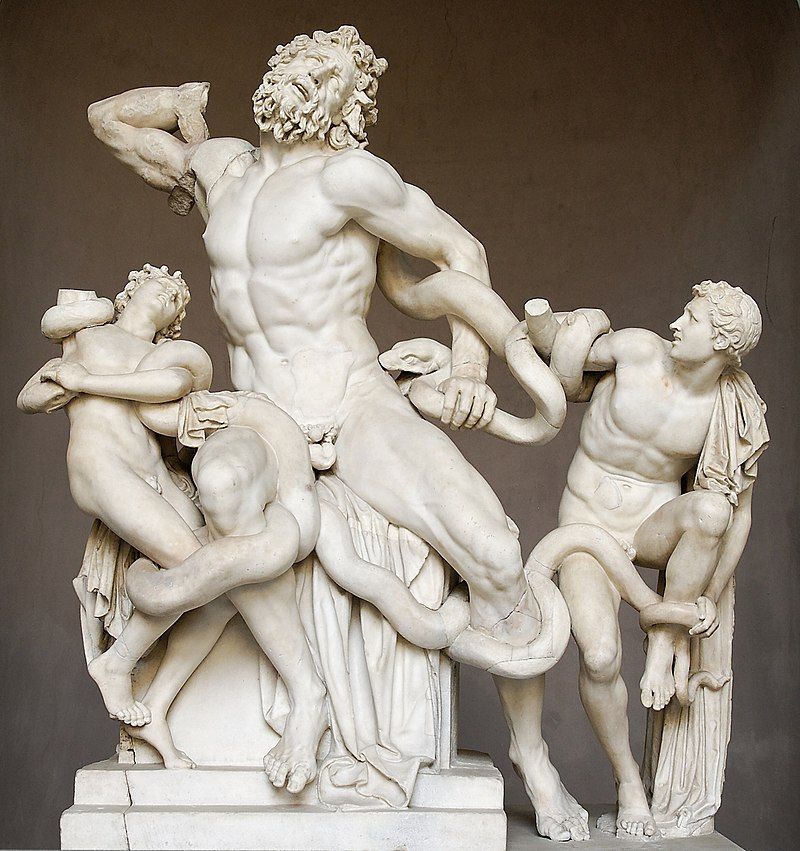

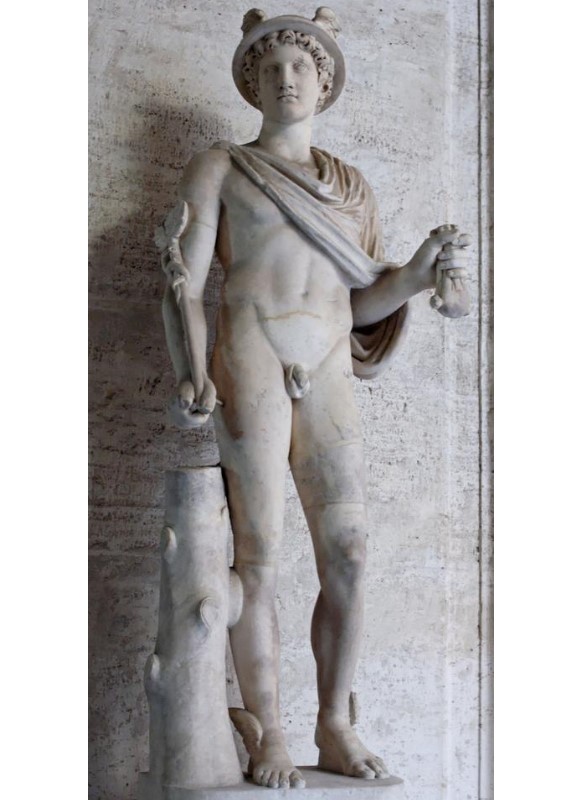

Hermes,

Roman copy of a Greek original, marble, Capitoline Museums, Rome

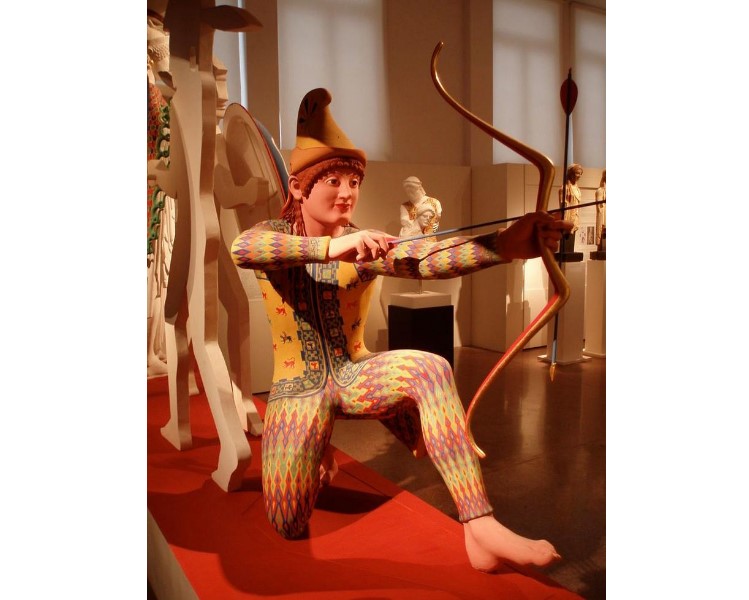

Mercury

Distinctive Sign: A small round hat, wings on his ankles and a sceptre known as caduceous

Profession : God of travellers, merchants… and also robbers!

Key fact: While he was still a baby, he very craftily stole his half-brother Apollo’s flock

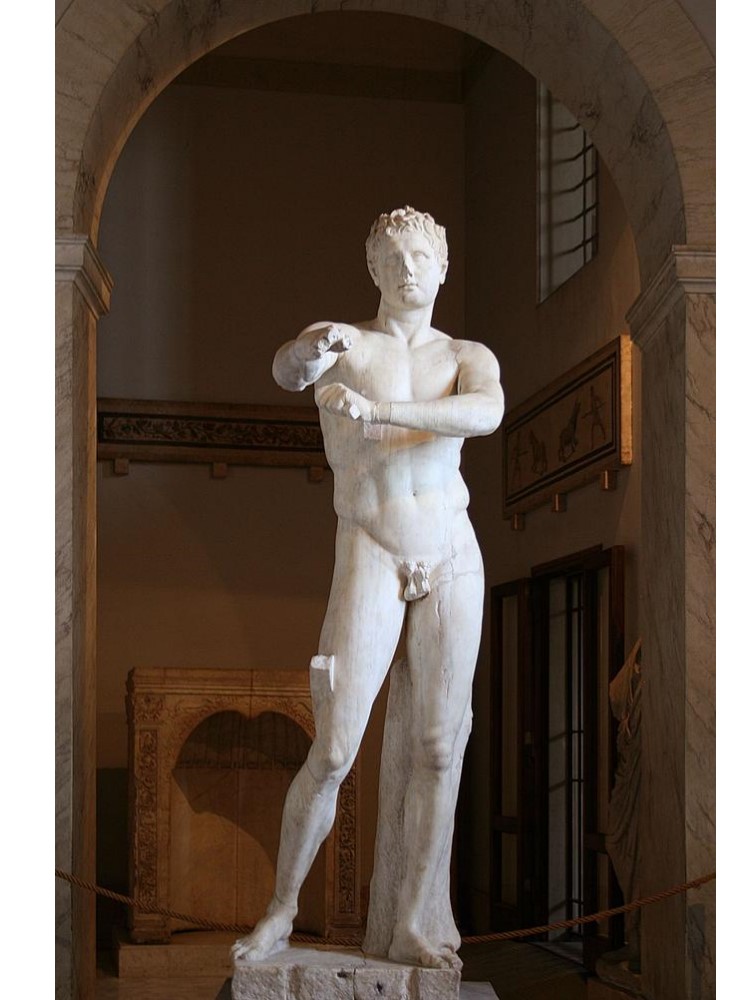

Colossal Statue of Mars,

Second century, Capitol Museum, Rome. Photo: Jean-Pol GRANDMONT, CC BY 3.0

Mars

Distinctive Sign: His armour, a sword, sometimes with a dog or a wild boar

Profession : God of war, violence and bloody crimes

Key fact: The Romans reserved special honour for him. He was never far from his friends Discord, Terror or Grief.