South Façade of the Opera Garnier in Paris,

Charles Garnier, built between 1861 and 1875. Photo: Peter Rivera, CC BY 2.0

The Grand Staircase

Charles Garnier, built between 1861 and 1875. Photo: isogood, CC BY-SA 4.0

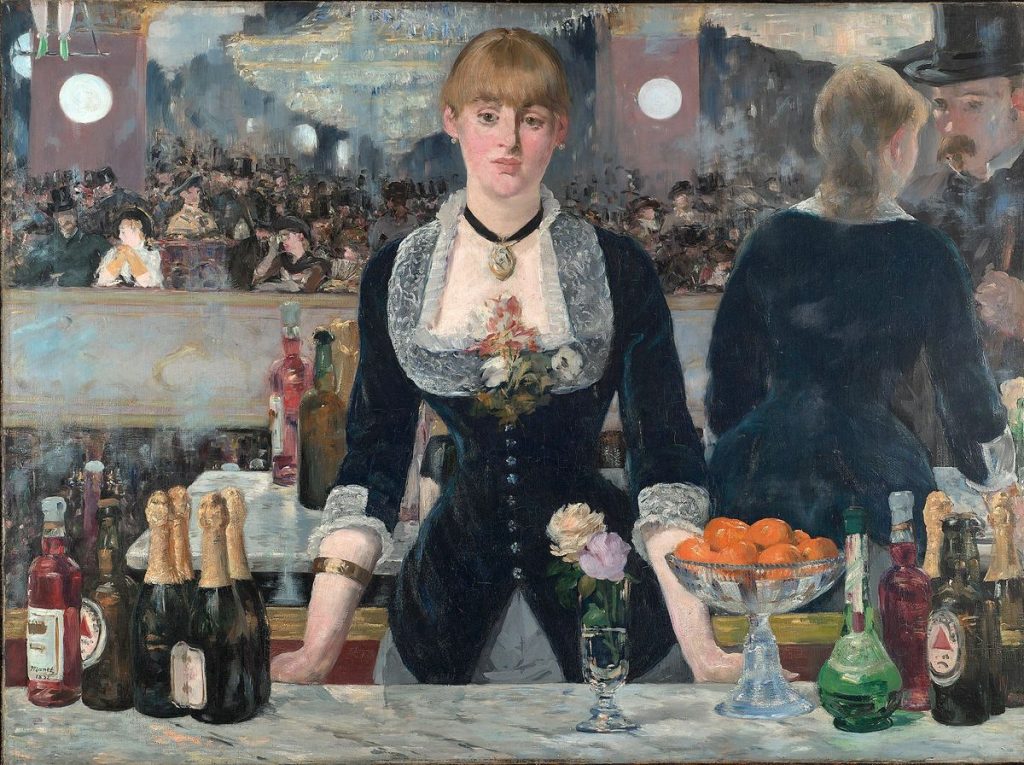

The Grand Entrance Hall,

Charles Garnier, built between 1861 and 1875. Photo: Eric Pouhier, CC BY-SA 4.0

The Theatre Hall,

Charles Garnier, built between 1861 and 1875. Photo: Chris Chabot, CC BY-NC 2.0