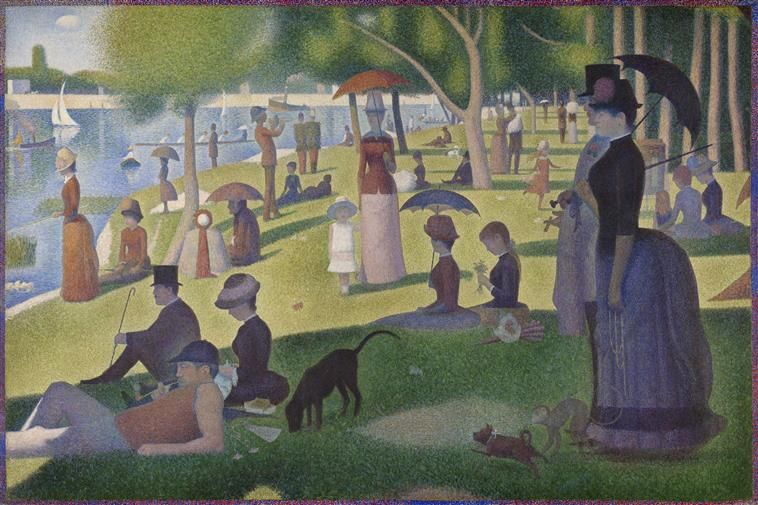

The 1886 exhibition stands out for the variety of artists and styles it includes. The participation of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, new recruits, isn’t universally supported as their painting heralds new directions. The two young recruits, who were brought in by Pissarro, prefer to use touches of pure colour, basing their practice on scientific principles – in contrast to the freer, more spontaneous approach taken by their predecessors, the impressionists: they’re practitioners of divisionism.

Six years have passed since the previous edition in 1882 and the art world is evolving rapidly. A clientele is developing for impressionist painting, and new ways of exhibiting, often solo shows, are enjoying growing success. Our protagonists are disbanding, with many of them settling a long way from Paris… The 1886 exhibition will be the last.

The rich and eventful history of impressionist exhibitions shows us that the one and same ideal brought these very different artists together for a while: a great burst of independence and freedom!

The last of those eight collective events, the 1886 impressionist exhibition marks the end of an era during which these artists shared a common ideal of artistic independence and freedom.

An episode produced under the academic supervision of Anne Robbins and adapted from her lecture “The Impressionist Adventure · The Exhibitions”.

But tensions are already appearing among the exhibitors. Two questions divide the group:

In 1882, given the climate of disagreement, a number of critics wonder if it’s already the end of impressionism.

Disagreements on the thorny subjects of participation in the Salon and the profile of new exhibitors create tensions.

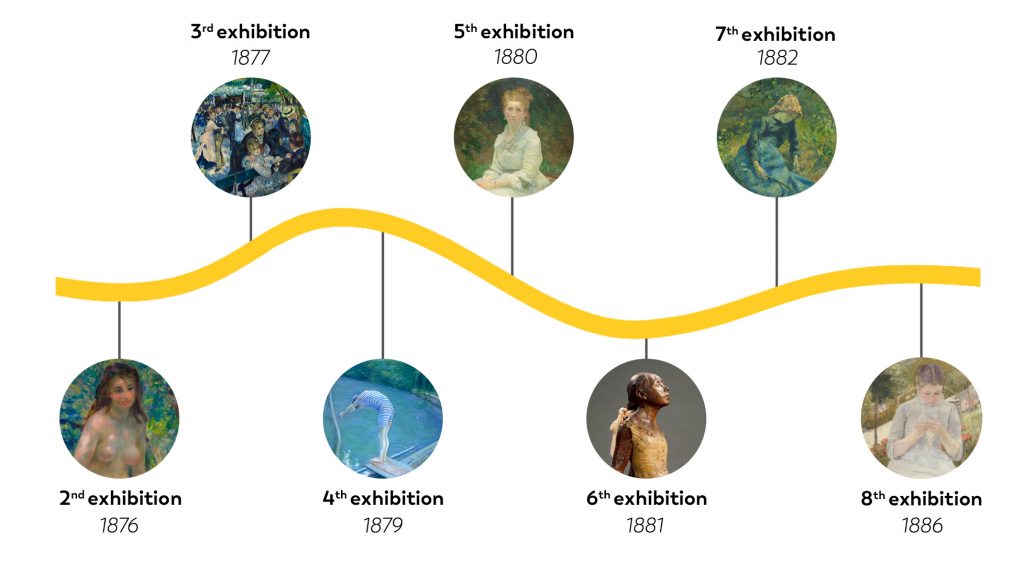

Among the eight exhibitions, the third edition, held in 1877, stands out for its remarkable unity.

The works in the exhibition, this time in a rented apartment in Rue Le Peletier, are remarkably homogeneous.They assert the principles of the “new painting” loud and clear! It’s also on this occasion that the group’s artists use the term “impressionists” for the first time, in their exhibition banner and as the title of their newly founded art magazine.

Another grand première: the exhibition is well received and makes a profit. Buyers include the painter Caillebotte in person. He uses his fortune to support his friends!

The third exhibition in 1877 really puts impressionism on the map as a new, coherent and unified form of painting drawing its subjects from nature, the open air and the modern world.

Eight impressionist exhibitions, of various sizes, are held between 1874 and 1886.

Despite the first exhibition’s financial failure, the impressionist painters don’t give up! Between 1874 and 1886, they hold eight exhibitions that include a total of 58 different artists.

So the group of exhibitors continues to evolve, with dropouts and new recruits along the way. Although profiles remain varied, certain artists emerge as key figures in the movement:

Paul Cézanne (1939 – 1906) was amongst the artists whose submissions were refused by the Salon and exhibited three works in the first impressionist exhibition in 1874. However, he leaves the group in 1877 and sets off on his own artistic journey. Conversely, other artists join the ongoing adventure, including Gustave Caillebotte and the American painter Mary Cassatt.

Over the course of the eight impressionist exhibitions, the group of artists who participate in them continues to evolve.

1874 sees a grand première: tired of the Salon’s repeated refusals, these artists mount their own independent exhibition. It’s up to them to decide which works to present and how to present them! What counts most is solidarity: commissions are charged on sales of paintings and they have to be shared fairly among the participants.

On 15 April, the exhibition opens its doors at 35 Boulevard des Capucines in Paris, in the former studios of photographer Félix Nadar. Curious to know what there is on show there? Then off we go for a private visit!

There’s our little group of “independent” artists. And a good many critics muttering in front of these “daubers” who are exhibiting paintings of “impressions” that the public deem slapdash, unfinished.

And they aren’t the only ones to try their luck!

A number of academic artists, no strangers to the Salon, also take part, tempted by the idea of an independent exhibition. Such is the case, for example, with Auguste Ottin and Alfred Meyer.

Assessment? Although it’s a financial disaster, as only four paintings are sold, the exhibition is seen by a good many art lovers and critics and has caught people’s attention. It’s a glorious feat!

Later, it will be seen as marking the “official” beginning of impressionism.

The 1874 exhibition brings together artists from a variety of backgrounds but connected by a common desire: to exhibit together, independently of the Salon. It’s one of impressionism’s founding events.

In the 1860s, an informal artist collective, including Monet and Renoir, congregates in Paris around shared ideas. Their goal? To provide an alternative to official, “academic” art, which is subject to specific, unchanging rules.

The style of art taught in Schools of Fine Art is based on rigid principles and well established themes: historical, mythological and religious subjects for the most part.

In contrast, this group of artists, who aren’t yet known as “impressionists”, consider that painting should be a means of capturing the moment, whether it’s a changing sky or rapidly changing world around them. To this end, they develop a completely different method and a new approach:

They paint “sur le motif”, i.e. outdoors in the open air, in order to study the effects of light;

Unfortunately their works are often refused by the jury of the Salon, France’s main official art exhibition held by the Academy of Fine Arts. So they come up with the idea of organising their own exhibitions to show their works and find buyers without having to depend on the Salon.

In 1874, it’s a done deal: the year sees the first of a series of exhibitions that would eventually be described as impressionist.

In the 1860s, painters opposed to academic art begin to think about organising their own exhibitions.

To wrap up (sorry, terrible pun), let’s look at the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude who had a habit of wrapping objects, and not just small things like these cans, but cars, buildings, and even bridges!

During their career, Christo (1935-2020) and his wife and partner Jeanne-Claude (1935-2009), wrapped the Reichstag government building in Berlin, and ran 200,000 metres of white nylon cloth across California.

These monumental projects created dramatic new ways of looking at cities and landscapes, transforming the familiar into something entirely new.

Most projects have taken decades to be realised, including L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped for which planning began in 1961 and was only completed after Christo’s death. This final undertaking involved wrapping the Arc de Triomphe in Paris with 700 ropes and masses of fabric.

With the materials moving in the wind and reflecting the sunlight, they wanted to create a “living object” so that “people will want to touch” it.

Still life is alive and kicking in the 21st century. Artists continue to reinvent and transform everyday objects, making the ordinary extraordinary.

It’s not unusual for artists to work with other people. For example, medieval and Renaissance artists had workshops packed full of apprentices, and Andy Warhol had teams of assistants to make his work. Let’s face it, most art “movements” are essentially about groups of friends – or sometimes rivals – exploring ideas and pushing boundaries together.

These days, it’s common for artists to make work with everyday people like you and me. Sometimes they just need extra pairs of hands, while at other times collaboration can give an artwork unique and special qualities.

American conceptual artist Mark Dion asked a group of volunteers in London to help him to scour the shores of the River Thames to see what they could find. Together, they collected hundreds of objects such as clay pipes, plastic toys, and animal bones, which were placed in this old–fashioned cabinet, full of stories and mystery.

Now these really were found objects!

Austrian artist, Erwin Wurm, has a quirky way of getting people involved in his art too. He invites participants and performers to react to written instructions involving everyday things like clothes, buckets, balls, you name it! They might end up squeezing into clothes, balancing on buckets, or even hugging a watermelon. And get this: there’s a strict one-minute time limit, so there’s no time to overthink!

Artists often work collaboratively with people to make their artworks, including finding disparate objects to make a whole.

In the 1960s artists used video art and photography to capture their everyday, paving the way for Wolfgang Tillmans to photograph his socks! Clean ones thankfully…

This dull, domestic moment featuring some socks thrown onto the sofa, waiting for someone to put them away. It looks like a casual snapshot which has been taken almost by mistake. However, the photograph is deceptively casual. German-born photographer Wolfgang Tillmans makes highly staged compositions, putting a lot of time into setting up his still life arrangements. Tillmans is encouraging us to look at things without pre-determined values.

This film is another interpretation of the Still Life genre, made possible by the medium of film. Although its theme – time passing – is as old as the hills, this time–lapse video of fruit rotting may not have taken as long to make as a Dutch master painting, but still conveys grace in the decay.

Apparently some of the fruit, particularly the peaches, were so genetically modified that they took much longer to decompose than normal!

Sam Taylor-Johnson adds another hint that this is not a traditional still life, can you spot it?

Artists have used photography and film to capture and hold particular moments in time, from time–lapse videos showing nature decaying, to casual yet staged compositions.

"*" indicates required fields