Cornelia Parker, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View,

1991. Wood, metal, plastic, ceramic, paper, textile and wire. © Cornelia Parker Photo: Tate

Hugo Glendinning, Cold, dark matter, an exploded view

(The Explosion), © Hugo Glendinning

Having progressed from sculpture, installation as an artform started to gather momentum through the 1960s. Usually, they are large-scale constructions made out all kinds of objects and materials, which can be personal, abandoned, collected, and sometimes literally rubbish, like junk or scrap. They also tend to be arranged as “environments” for audiences to walk around and interact with.

British artist Cornelia Parker made this installation by blowing up a shed – yes, blowing up a shed! – and then putting it back together. She even called in the British Army to do it. Why? To transform the objects into something new.

The shed is no longer a place where things are safe and stored, but something that has been exploded into hundreds of scattered pieces. And yet the pieces are suspended in the process of scattering, and the explosion becomes a thing of beauty and contemplation.

Installations use materials, including found objects and readymade objects, to create structures or whole environments which audiences can interact with.

Let’s stay in the world of the contemporary as we explore how artists have been invigorating the genre of the still life in more recent years.

It makes sense to start this chapter with one of the most remarkable – and loved – takes on the found object and the readymade in the 20th century, a film called The Way Things Go by Swiss duo Peter Fischli and David Weiss. What happens in it? Well, what doesn’t?! A crazy chain reaction of household and industrial objects like ladders, tyres, kettles, chairs, metal drums, bulbs, pans, and fireworks (yes, there are pyrotechnics!) lean, crash, bump, and explode into each other in a massive warehouse.

Lasting half an hour, the cinematic sequence is made up of over two dozen clips filmed over a period of two years. As each new object takes centre stage and performs its part, there are consequences to the actions of each object – yet there is a resilience in the way the sequence continues. In the 1980s Fischli and Weiss became fascinated with states of impending collapse, and this example shows that tension between order and chaos!

The Way Things Go by Fischli and Weiss made the found object noisy, unpredictable, fun, and violent, bringing objects to life in extraordinary ways.

Surrealism was a close descendant of Dadaism, with its taste for the uncanny and absurd, and a strong desire to shock the Art Establishment (the mainstream of ideas around art formed by the major art institutions and art dealers). It started life in 1920s Paris as a literary movement sparked by French poet André Breton who wrote the first Surrealist manifesto – La Révolution surréaliste – in 1924.

Because it was highly influenced by the theories of the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, Surrealism went beyond the disruptive tendencies of the Dada movement, digging into the realms of psychology and the unconscious mind. As well as influencing film, photography, literature and painting, Surrealism took found objects to a whole new level by combining them in disturbing and humorous ways.

Take, for example, the bizarre joining of objects in Dali’s Lobster Telephone, Meret Oppenheim’s teacup lined with gazelle hair, or Dorothea Tanning’s mutated roses. They’re like bad dream. Anyone fancy a cuppa and a chat?

Surrealist artists brought together bizarre combinations of found objects so that the finished piece was uncanny, disturbing, funny, or dreamlike.

There’s no doubt about it, the legacy of Pop Art is massive, and ongoing, with the use of the readymade and continued references to mass production and cultural iconography.

Ai Weiwei is one such artist whose work has even been exhibited alongside Andy Warhol’s, exploring the parallels of their work despite being from different geographical locations and time periods.

Where Warhol chose Coke bottles to comment on capitalism, Ai Weiwei paints the Coca-Cola logo on an ancient Chinese urn to comment on communism, creating his own subversive symbolism. They both make direct references to Duchamp, Warhol with Screen Test: Marcel Duchamp, 1966 and Ai Weiwei with Hanging Man in Porcelain, a portrait of Duchamp fashioned from a coat hanger.

And what about Damien Hirst, one of the original YBAs (Young British Artists)? His work and attitude kickstarted a renewed interest in contemporary art following the irreverent and fearless 1988 Freeze exhibition he curated while still a student. Hirst uses humour, irony, and everyday objects in his work, from dead animals cut in half or pickled sharks, to mass-produced Spot Paintings and pharmaceutical packaging.

Hirst’s series The Last Supper is a visual irony on our human relationship with pharmaceuticals. He comments on how we have replaced our faith in religion with our faith in medicine. It makes us think about how much medicine has become part of our regular diets, and how bad our actual diets can be for us.

His work shares the themes of Dutch 17th century still life paintings, as well as the work of Andy Warhol and the Pop Artists – death, wealth, religion, mortality and consumerism.

The legacy of Pop Art is all around us, in the work of other artists, and in contemporary advertising, packaging, and visual culture.

Some artists, like the sculptor and graphic artist Claes Oldenburg, made Pop Art–inspired objects on a gigantic scale.

This enormous ice–cream cone, for example, seems to have fallen from the sky and plopped onto the corner of a building in Cologne, Germany.

He made this with his partner Coosje van Broggen with whom he collaborated for over 30 years. His dramatic take on still life objects has been staggering – from soft sculptures of hamburgers and chips to public sculptures across the globe.

Another example of a contemporary artist building on the popularity of Pop is Jeff Koons. His colourful Pop sculptures, like Balloon Dog (Yellow) are characterised by their form – taken from balloons traditionally twisted into the shape of animals by clowns. Imagine a balloon dog blown up to over three meters tall, but instead of rubber, it’s made of polished metal with a dazzling, shiny surface!

Many artists took the dynamism of Pop Art and magnified still life objects into public art works on a colossal scale.

Some of the most recognisable works of Pop Art are by American artist Roy Lichtenstein. He is known for taking the style and subjects of cartoons and comics and making them into captivating, large–scale pieces. His work is highly stylised and flat, comes mainly in primary colours, and is, well, very popular!

In the 1970s Lichtenstein explored ideas around “high art” which included traditional kinds of still life. For example, this print includes a “classic” arrangement of fruit which harks back to traditional still life paintings. It also includes a portrait, but is updated to become the kind of stylised woman you would find in a comic, movie, or advert of the time.

Lichtenstein’s approach to Pop Art was inspired by cartoons and comics.

Andy Warhol, an icon in his own right, transformed ordinary objects into cultural icons, immortalising items like Coca-Cola bottles, Brillo boxes, and Campbell’s soup cans into fully-fledged artworks. His penchant for elevating the mundane to the extraordinary reshaped the artistic landscape, challenging traditional notions of what constituted art.

Warhol’s fascination with repetition and mass production was evident not only in his art but also in his daily routine, consuming Campbell’s soup everyday for 20 years. This penchant for repetition found its artistic expression in techniques like screen printing, enabling Warhol to replicate images with varying colours, mimicking the mass-produced aesthetics of advertising billboards.

By leveraging mechanised processes like screen printing, Warhol blurred the lines between art and commerce, creating works that were not only visually striking but also commercially viable, reflecting his background as a commercial artist and his keen eye for the intersection of art and consumer culture. Yet, Warhol’s multifaceted career, spanning filmmaking, fashion design, and public relations, underscores his complex identity as not merely a machine-like creator, but also a savvy businessman with a diverse array of interests and talents.

Andy Warhol gave everyday objects iconic status by employing mechanised techniques like silkscreens to rapidly produce nearly identical images at huge scales.

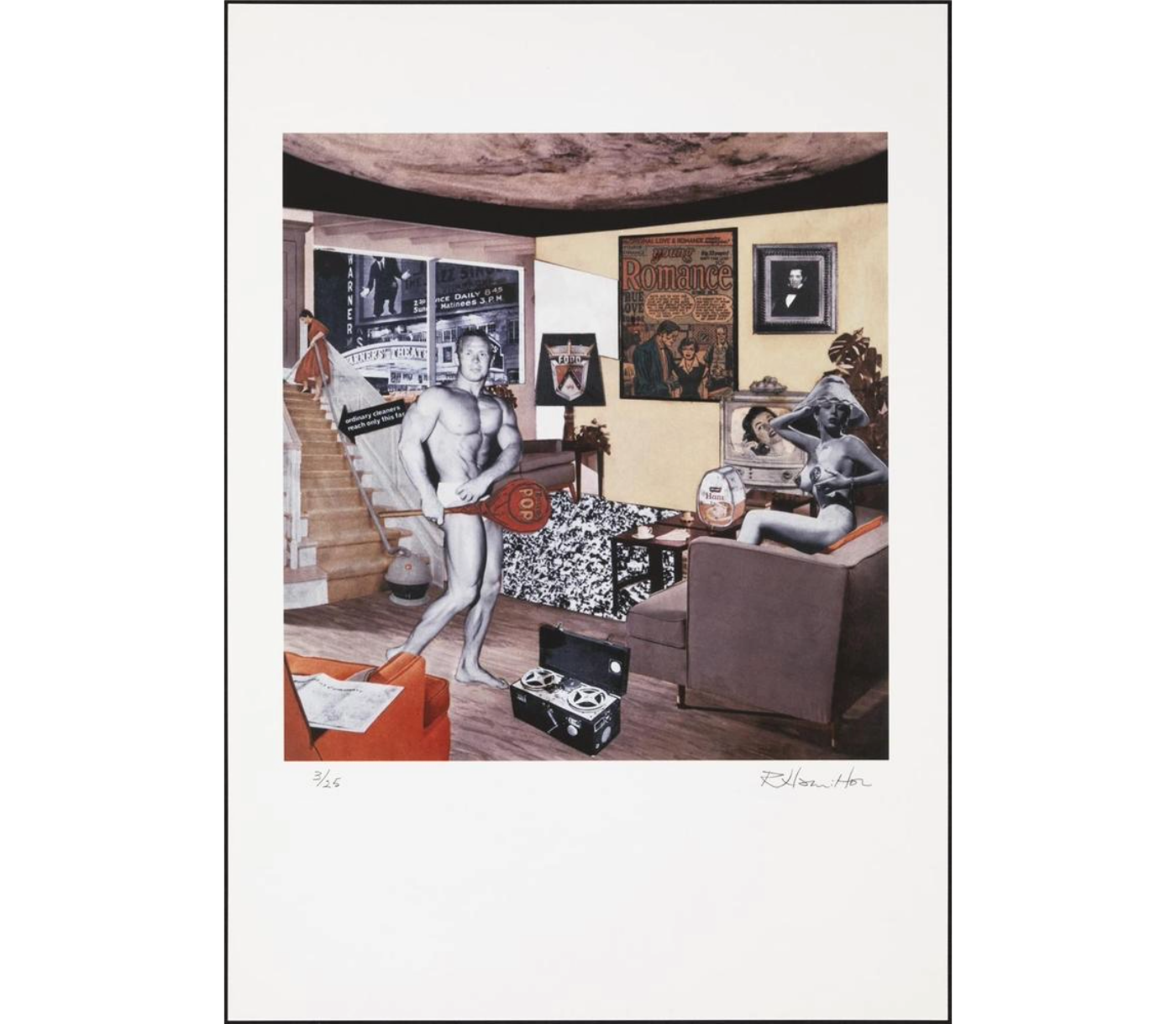

What makes Pop Art pop? British artist, writer, and teacher Richard Hamilton gave a pretty good summary above. But what’s all this got to do with still life? The subject matter – everyday objects! While Pop Art borrowed the aesthetic of mass media and mass production, such as the bold colours, clean lines, and the Ben Day dots of comics and product packaging, it also drew on popular objects of the day – which were low–cost and mass–produced.

Pop Art was bold, bright, and ironic, underpinned by fascination with popular culture, consumer culture, and mass production.

Where and when did Pop Art start? When we think of Pop Art, it’s often American giants like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein that spring to mind. But in fact Pop Art emerged in the 1950s in both the UK and the USA at around the same time.

The Independent Group (London, 1952 – 1955) were painters, sculptors, architects, writers and critics who wanted to challenge prevailing modernist approaches to culture.

While artists from The Independent Group in London, such as Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton, and other British artists such as Pauline Boty and Peter Blake were populating their collages with comics, adverts and celebrities, American artists Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg were also placing everyday objects like flags and newspapers into their work.

Although British and American Pop Art had different styles and techniques, especially as each developed in the 1960s, both wanted to break down barriers between so called “high” and “low” art. Even though the world had by now experienced Cubism, Surrealism and the found object, it hadn’t considered popular culture as art.

Hmmm, it seems like we’re getting back to those hierarchies again.

Pop Art broke down the barriers between “high” art and “low” art, using materials and subjects from everyday life.

Before we round off this chapter, let’s think about some of those less dramatic artworks which sit within the world of the found object – the overlooked or seemingly mundane. The idea of the chance encounter came from Surrealism, celebrating the bringing together of unlikely objects and materials.

Many artists take found and forgotten objects and invite us to look at them more closely. Some prompt us to imagine an object’s story, like Cornelia Parker’s The Spider That Died in the Tower of London, while others raise questions about how we are treating the planet, like Simryn Gill’s photograph of rubbish washed up by the tide.

Chance encounter – an idea that came from Surrealism and celebrated the bringing together of unlikely objects and materials.

Many artists encourage us to look more closely at forgotten or overlooked, everyday objects.

"*" indicates required fields