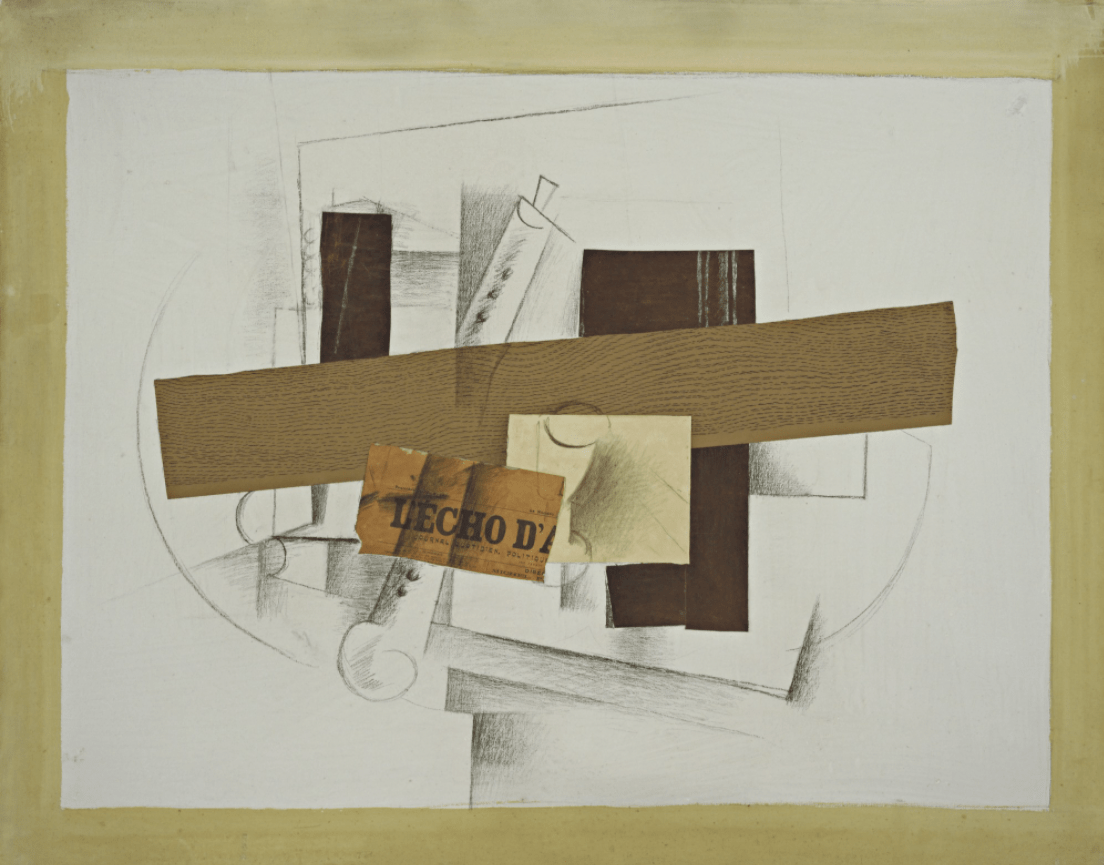

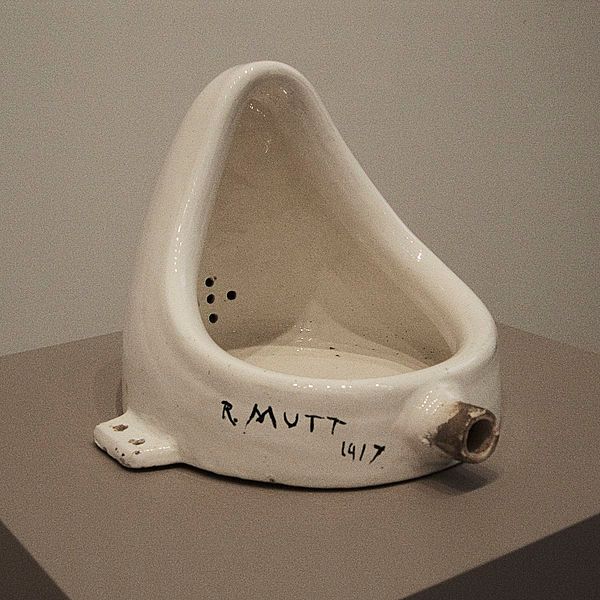

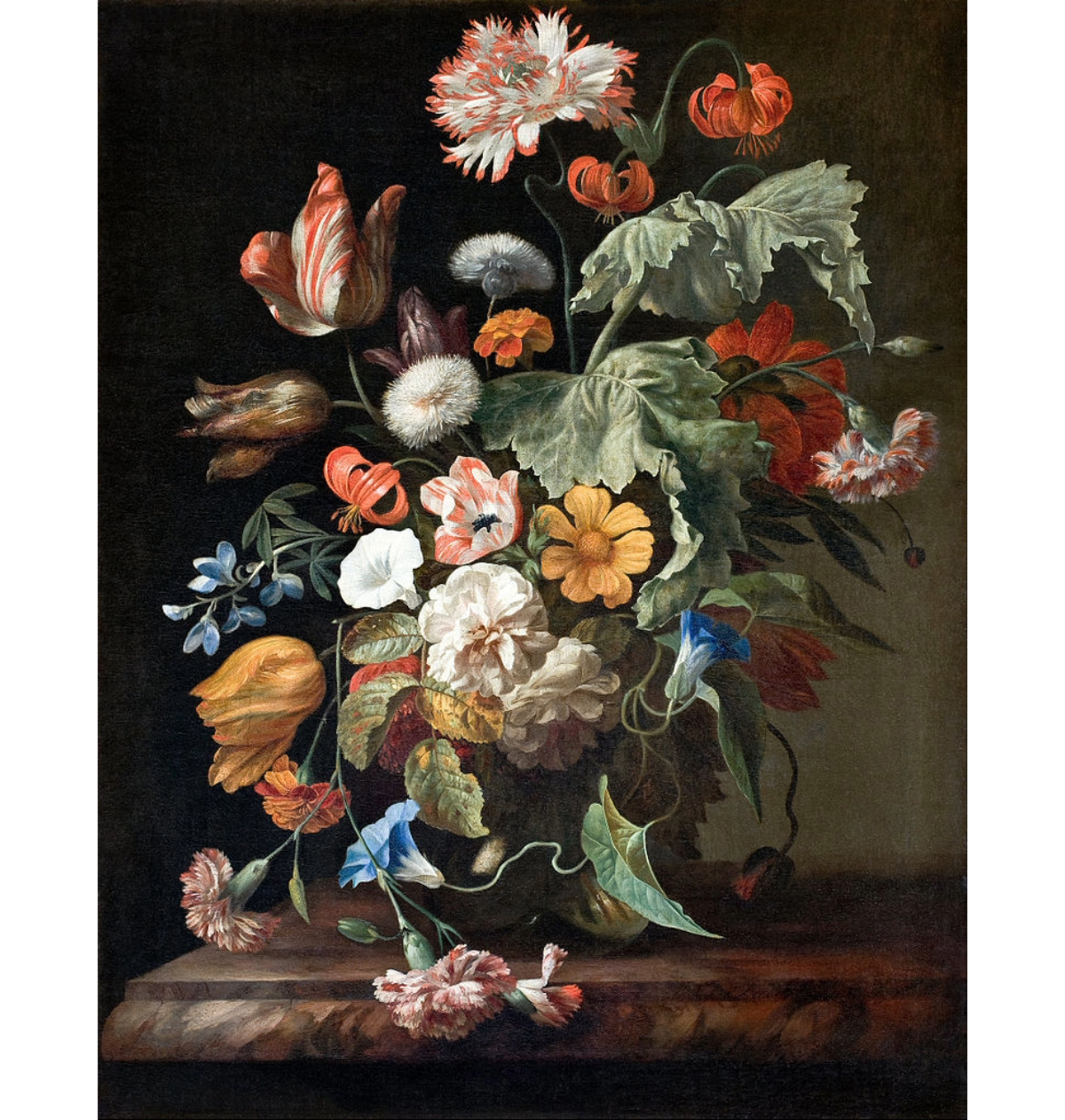

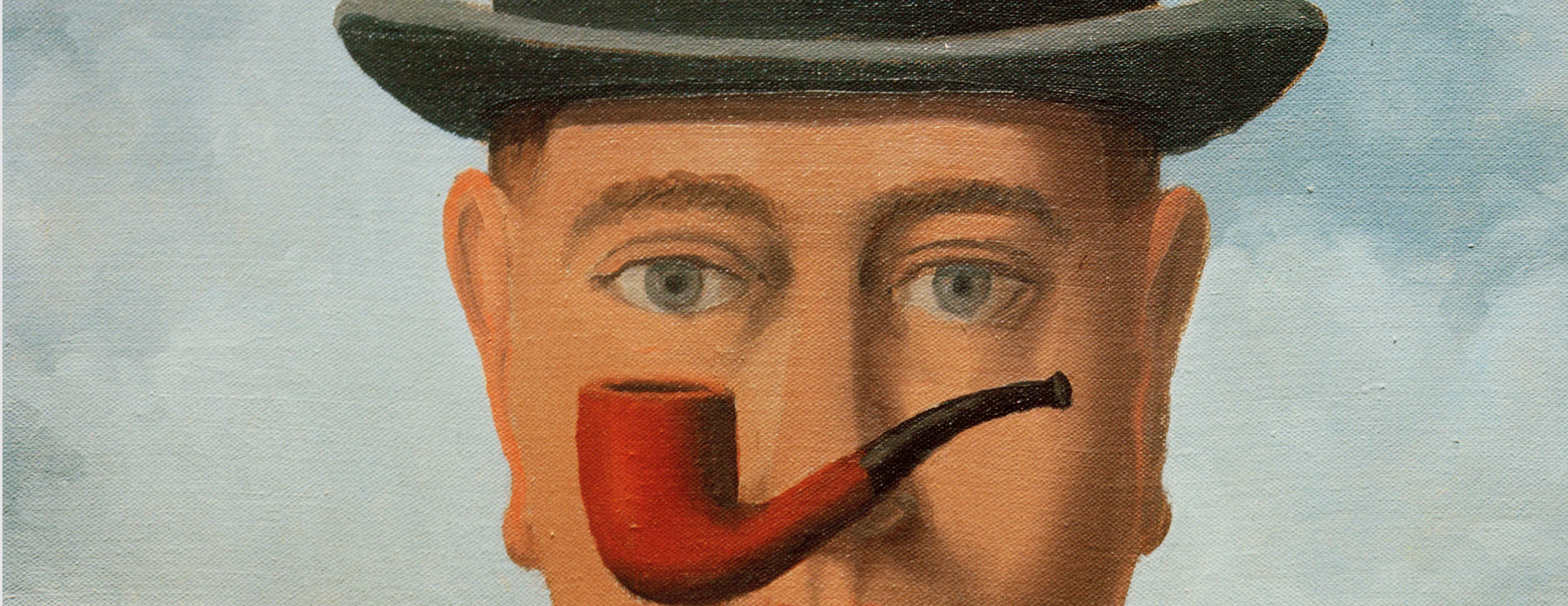

This is a still life. But what does that mean? That the objects are still? Yes. That they do not move? Yes. That it is a representation of life, so it shows things that are alive? No. Well, sometimes yes, but often they are dead, or dying.

In essence, still life is a subject in art that refers to anything that does not move – an inanimate object which can be natural or humanmade, or, frankly, dead.

But where does the term come from?

While still life as a subject in art has been around for literally ages – for example, it has been found in Ancient Egyptian tombs, and pops up all over the place in medieval and Renaissance altarpieces; it only became used as an actual term in the 17th century Netherlands.

The English term “still life” stems from the Dutch “stilleven”, which means “quiet life”. The French called it nature morte and in Italy it became natura morta which both mean “dead nature” – except, remember, not everything in a still life is dead…